Leetcode M808 Soup Servings Convergence Analysis

M808 description:There are two types of soup: type A and type B. Initially, we have $n$ ml of each type of soup. There are four kinds of operations: 1. Serve 100 ml of soup A and 0 ml of soup B, 2. Serve 75 ml of soup A and 25 ml of soup B, 3. Serve 50 ml of soup A and 50 ml of soup B, and 4. Serve 25 ml of soup A and 75 ml of soup B. When we serve some soup, we give it to someone, and we no longer have it. Each turn, we will choose from the four operations with an equal probability 0.25. If the remaining volume of soup is not enough to complete the operation, we will serve as much as possible. We stop once we no longer have some quantity of both types of soup. Note that we do not have an operation where all 100 ml's of soup B are used first. Return the probability that soup A will be empty first, plus half the probability that A and B become empty at the same time. Answers within $10^{-5}$ of the actual answer will be accepted. Constraints: $0<=n<=10^9$

It's not difficult to find the algorithm, if one notices the recursive nature of the problem: State $(A,B) \rightarrow (A-100,B)$ or $(A-75,B-25)$ or $(A-50,B-50)$ or $(A-25,B-75)$.

But the upper bound of $n$ is $10^9$. Are we supposed to build a $10^9$ by $10^9$ table? How much time would that take?

It's easy to see that we can simplify the conditions a little bit. Apparently if the quantity is not a multiple of 25, the situation is the same as when the quantity is the next multiple of 25. So let's convert $n$ to the ceiling of its ratio to 25.

Now we can change the 4 operations to: $(m,n) \rightarrow (m-4,n-0)$ or $(m-3,n-1)$ or $(m-2,n-2)$ or $(m-1,n-3)$.

So it's easy to tell that the probability to win from the state $(m,n)$ is, $p(m,n)=\frac{1}{4}(p(m-4,n-0)+p(m-3,n-1)+p(m-2,n-2)+p(m-1,n-3))$.

The base cases are, $p(m,n)=\begin{cases} 0 & \text{if $m>0,n\leq0$}\\ 1 & \text{if $m\leq 0,n>0$}\\ 0.5 & \text{if $m\leq 0,n\leq 0$}\end{cases}$.

We could apply this subroutine recursively until we reach one of the base cases, but that would be very inefficient. The first important thing is we should memoize the intermediate results. We can do that in multiple ways. I chose the bottom up approach, i.e. just build the entire table. And since the conditions don't change, once I have the table, I can simply take a value from the table for any input.

But still, that would be a $4\times 10^7$ by $4\times 10^7$ table. Can we do better than that?

Here's the second crucial thing to notice: The larger $n$ is, the higher the probability that soup A will be empty first becomes, because there's a higher chance that we will serve more soup A than soup B in each step, we would expect soup A to decrease faster than soup B. If it keeps increasing, we can stop at the $n$ such that $p(n,n)>1-10^{-5}$, because for larger inputs, the difference between the result and 1 is always less than $10^{-5}$, so we can simply return 1!

The following program, which I submitted, is based on this intuition. It took 0ms, pretty fast.

```cpp

vector<vector<double>> tab;

bool first=true;

int oneTh=INT_MAX;

double check(int i,int j){

if(i<0) return (1.0+(j>=0))/2;

if(j<0) return 0;

return tab[i][j];

}

double avg(int i,int j){

if(i==-1){if(j==-1) return 0.5;return 1.0;}

if(j==-1) return 0.0;

return 0.25*(check(i-4,j)+check(i-3,j-1)+check(i-2,j-2)+check(i-1,j-3));

}

void init(){

first=false;

for(int n=1;n<=40000000;++n){

for(int i=0;i<n-1;++i) tab[i].emplace_back(avg(i,n-1));

if(1.0-avg(n-1,n-1)<0.00001){oneTh=n;break;}

vector<double> tmp;

for(int i=0;i<n;++i) tmp.emplace_back(avg(n-1,i));

tab.emplace_back(move(tmp));

// cout<<"n="<<n<<endl;

// for(auto& v:tab){

// for(auto e:v) cout<<e<<",";

// cout<<endl;

// }

}

}

class Solution {

public:

double soupServings(int n) {

if(first) init();

if((n=(n+24)/25)>=oneTh) return 1.0;

if(n==0) return 0.5;

return tab[n-1][n-1];

}

};

```

(In the submission page, all the sample submissions that take less than 100ms use some magic number like "if(n>5000)" or "if(n>10000)", but the threshold could be easily determined during the computation.)

The main reason for this article is not about the program, so let's go back to the assumption. The assumption is based on our intuition, but can we prove it rigorously? Let's think about it!

The editorial of that problem on leetcode demonstrates the law of large numbers. But the fact that the probability converges to 1 doesn't justify the statement that after we first encounter a value $\geq 1-0.00001$, all the values afterwards satisfy it too.

Consider the function $f(x)=e^{-x/100}\cos^2(x/100)$. We know that it converges to 0 as $x\rightarrow\infty$, but that doesn't mean that we can stop when we encounter a value less than the criterion for the first time, because the values will keep increasing and decreasing alternately! So what we really need is a proof that it increases monotonically, or an upper bound such that even if it starts to increase again, it will never exceed the upper bound.

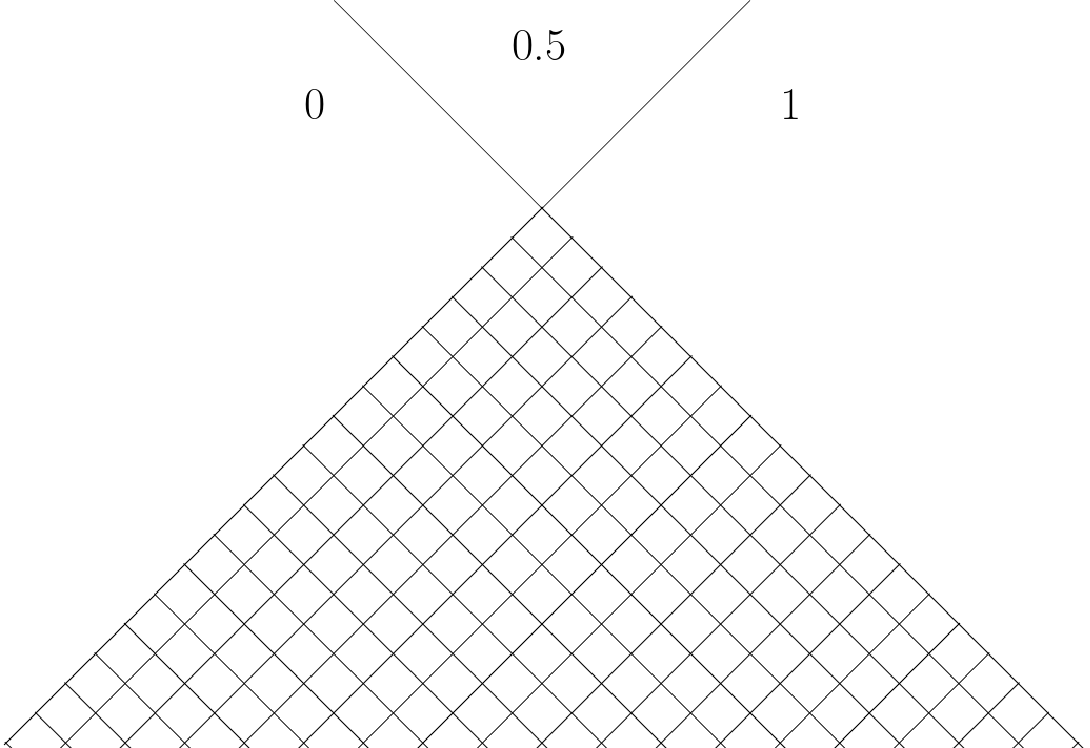

The probabilities that we calculate form a table, which we can represent as a grid graph. To make it easier to see, let's rotate it by $45^{\circ}$:

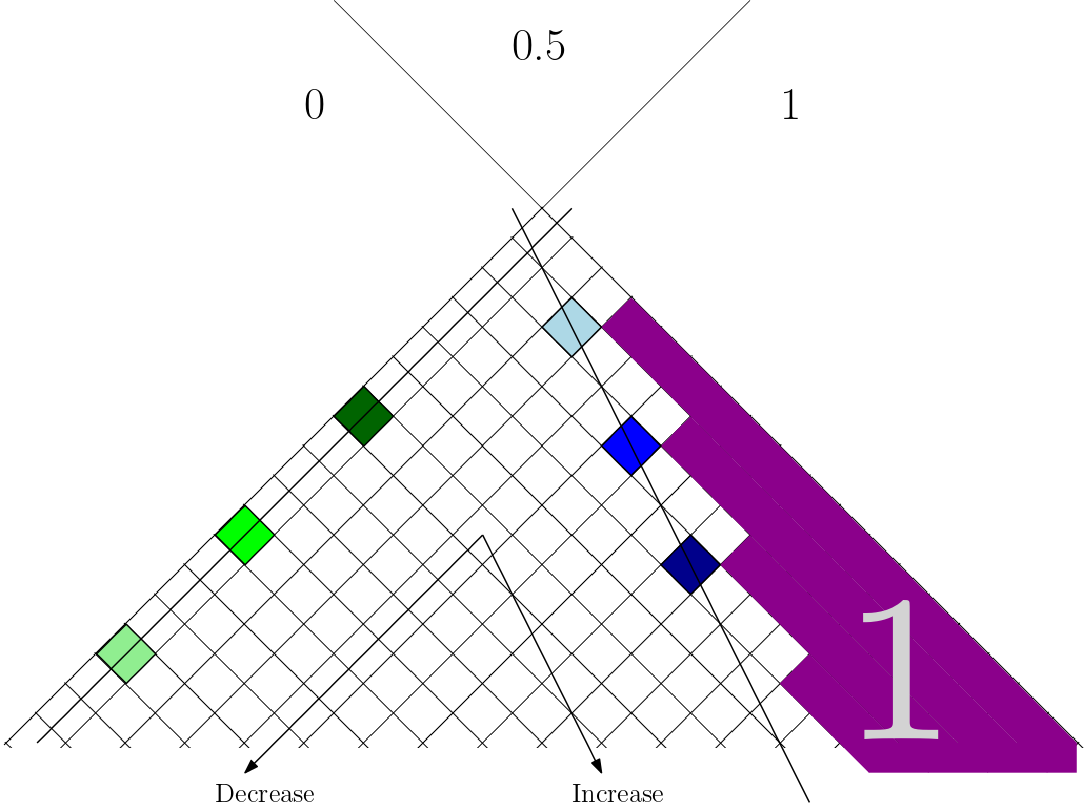

The value at each cell is the average of another 4 cells, and if the cells are outside the grid, the value is 0 or 1 or 0.5 respectively in the regions shown on the figure:

(From here, immediately we find two optimizations to our program: First, it's unnecessary to calculate half of the numbers in the grid. Because we only need the values at $(n,n)$, all the elements that we'll ever use are either in $(odd,odd)$ cells or $(even,even)$ ones. Second, we only need one layer of the values to construct the next layer. So instead of saving the entire table, we could just use two vectors to store the current layer and the next layer, which saves a lot of space. That will do for all odd $n$s, then we do the same to fill in all the even ones. Another possible optimization is, to find the last $p(n,n)$, we just need the values of the cells between these two lines, so we can start to shrink the vectors after half way through, which cuts the space complexity by half again. But that's only if we already know the last value of $n$, and it's probably going to be a little more complicated to implement.)

(From here on, "next layer" means two rows downwards, e.g. from coordinate (1,1) to (3,3) is one layer down.)

What we want is, a proof that the values at the cells in the middle increases monotonically as it goes downward, or an upper bound of those values as a function of the number of steps.

Since we've seen the law of large numbers, maybe we can continue on that path?

The central limit theorem states that with i.i.d variables, their average will converge to normal distribution.

The problem can be seen as a random walk: We start at the origin, each time we may take 1 step left, or no move, or 1 step right, or 2 steps right, each with probability 1/4, and we want to find out the probability that we are at location $l$ after $n$ steps. It's easy to find the expectation of the variables $\mu_0=(-1+0+1+2)/4=1/2$, and the variance $\sigma_0^2=(1+0+1+4)/4 - 1/4=5/4$.

If we start from $(n,n)$, we will move out of the grid in at most $\frac{n}{2}$ steps. By then, the range of our final location is $[-\frac{n}{2},n]$. The expectation of the summation is $\mu=\frac{n}{4}$. Let's show them on the figure:

If you're thinking "wait a minute - once we reach either one of the boundaries, we can't keep going, so how can we map the probability distribution along the boundaries to the line?", that's good thinking! Because indeed, it's not a one on one map. But we only cares about the summation of the probabilities, and notice that if our final location is in the 0 or 1 region, we must have come through the corresponding boundary, and if we come through either one of the boundaries, we won't be able to leave that region. That means, the summation of the probabilitese from $-\frac{n}{2}$ to 0 and from 0 to $n$ corresponds to the probability of B empty and A empty respectively. There is a discrepancy, though, because if we reach the first 3 rows inside the grid, we may enter the 0.5 region. But as $n$ increases, that probability converges to zero.

So, let's compute the probability distribution of our final location on that horizontal line. The central limit theorem states that the probability distribution should converge to a normal distribution with expectation $\mu=\frac{n}{4}$ and variance $\sigma^2=\frac{5n}{8}$. The probability of A empty is

$$P=1-\int_{-\infty}^0 \mathcal{N}\left(\frac{n}{4},\sqrt{\frac{5n}{8}}\right) dx$$

We can manipulate the variable a little to convert it to an integration on the standard normal distribution:

$$P=1-\sqrt{\frac{5n}{8}}\int_{-\infty}^{-\frac{n}{4}\sqrt{\frac{8}{5n}}} \mathcal{N}(0,1) dx$$

$$=1-\sqrt{\frac{5n}{8}}\frac{1+\text{erf}(-\sqrt{\frac{n}{20}})}{2}$$

Now we can easily find out the threshold based on this approximation, in one line:

```cpp

for(int i=1;i<2000;++i) if((1+erf(-sqrt(i/20.0)))*sqrt(5*i/32.0)<0.00001) {cout<<"i="<<i;break;}

```

We get $i=230$, which corresponds to an original value of $230\times 25=5750$. The threshold I got from my program is $oneTh=179$, which corresponds to an original value of $4475$. How close is this approximation? Let's find out the differences:

```cpp

for(int i=1;i<tab.size();++i) cout<<setw(8)<<tab[i][i]<<" - "<<setw(8)<<(f=1-(1+erf(-sqrt(i/20.0)))*sqrt(5*i/32.0))<<" = "<<setw(8)<<tab[i][i]-f<<endl;

```

Output: 0.625 - 0.702813 = -0.0778132 0.65625 - 0.634 = 0.0222501 0.71875 - 0.600243 = 0.118507 0.742188 - 0.583299 = 0.158888 0.757812 - 0.576178 = 0.181635 0.785156 - 0.575349 = 0.209808 0.796875 - 0.578759 = 0.218116 0.817871 - 0.585105 = 0.232766 0.827637 - 0.593511 = 0.234126 0.844849 - 0.603362 = 0.241487 0.852173 - 0.614214 = 0.237959 0.866699 - 0.625739 = 0.24096 0.872559 - 0.63769 = 0.234868 0.884827 - 0.649881 = 0.234946 0.889633 - 0.662167 = 0.227466 0.900076 - 0.674438 = 0.225637 0.904058 - 0.686609 = 0.21745 0.913005 - 0.698613 = 0.214392 0.916344 - 0.7104 = 0.205944 0.924045 - 0.721932 = 0.202114 0.92687 - 0.733179 = 0.19369 0.933526 - 0.744121 = 0.189404 0.93593 - 0.754743 = 0.181187 0.941703 - 0.765035 = 0.176668 0.943762 - 0.774991 = 0.168771 0.948783 - 0.784609 = 0.164174 0.950555 - 0.793889 = 0.156667 0.954934 - 0.802832 = 0.152102 0.956464 - 0.811443 = 0.145021 0.960291 - 0.819727 = 0.140564 0.961618 - 0.82769 = 0.133927 0.964968 - 0.83534 = 0.129628 0.966121 - 0.842684 = 0.123438 0.969061 - 0.84973 = 0.119331 0.970066 - 0.856487 = 0.113579 0.972648 - 0.862964 = 0.109684 0.973525 - 0.869169 = 0.104356 0.975797 - 0.875113 = 0.100684 0.976565 - 0.880803 = 0.0957618 0.978566 - 0.886249 = 0.0923166 0.979239 - 0.89146 = 0.0877792 0.981004 - 0.896444 = 0.0845595 0.981595 - 0.901211 = 0.0803844 0.983153 - 0.905767 = 0.0773854 0.983673 - 0.910123 = 0.0735498 0.985049 - 0.914285 = 0.0707642 0.985506 - 0.918261 = 0.0672452 0.986724 - 0.92206 = 0.0646639 0.987127 - 0.925688 = 0.0614394 0.988204 - 0.929152 = 0.0590524 0.98856 - 0.93246 = 0.0561005 0.989515 - 0.935617 = 0.0538971 0.989829 - 0.938631 = 0.0511974 0.990675 - 0.941508 = 0.0491667 0.990953 - 0.944253 = 0.0466995 0.991703 - 0.946872 = 0.0448306 0.991949 - 0.949371 = 0.0425775 0.992614 - 0.951755 = 0.0408595 0.992832 - 0.954029 = 0.0388033 0.993423 - 0.956197 = 0.0372257 0.993616 - 0.958266 = 0.0353502 0.994141 - 0.960238 = 0.0339031 0.994312 - 0.962119 = 0.0321933 0.994779 - 0.963912 = 0.0308669 0.99493 - 0.965622 = 0.0293089 0.995346 - 0.967251 = 0.0280942 0.99548 - 0.968805 = 0.0266751 0.99585 - 0.970286 = 0.0255634 0.995969 - 0.971698 = 0.0242713 0.996298 - 0.973043 = 0.0232546 0.996404 - 0.974325 = 0.0220786 0.996697 - 0.975547 = 0.0211493 0.996791 - 0.976712 = 0.0200793 0.997052 - 0.977821 = 0.0192303 0.997136 - 0.978879 = 0.018257 0.997368 - 0.979886 = 0.0174819 0.997443 - 0.980846 = 0.0165967 0.99765 - 0.981761 = 0.0158893 0.997716 - 0.982632 = 0.0150846 0.997901 - 0.983462 = 0.0144392 0.99796 - 0.984252 = 0.0137078 0.998125 - 0.985006 = 0.0131192 0.998177 - 0.985723 = 0.0124545 0.998324 - 0.986406 = 0.011918 0.998371 - 0.987057 = 0.0113141 0.998502 - 0.987677 = 0.0108252 0.998544 - 0.988268 = 0.0102766 0.998661 - 0.98883 = 0.00983115 0.998699 - 0.989366 = 0.00933291 0.998803 - 0.989876 = 0.00892724 0.998836 - 0.990362 = 0.00847478 0.99893 - 0.990824 = 0.00810543 0.998959 - 0.991265 = 0.00769461 0.999043 - 0.991684 = 0.0073584 0.999069 - 0.992084 = 0.00698545 0.999144 - 0.992464 = 0.00667947 0.999167 - 0.992826 = 0.00634094 0.999234 - 0.993171 = 0.00606255 0.999255 - 0.9935 = 0.0057553 0.999314 - 0.993812 = 0.00550206 0.999333 - 0.99411 = 0.00522323 0.999386 - 0.994393 = 0.00499291 0.999403 - 0.994663 = 0.00473991 0.999451 - 0.99492 = 0.00453047 0.999466 - 0.995165 = 0.00430092 0.999508 - 0.995398 = 0.00411051 0.999522 - 0.995619 = 0.00390226 0.99956 - 0.99583 = 0.00372917 0.999572 - 0.996031 = 0.00354026 0.999606 - 0.996223 = 0.00338295 0.999616 - 0.996405 = 0.0032116 0.999647 - 0.996578 = 0.00306864 0.999656 - 0.996743 = 0.00291323 0.999684 - 0.9969 = 0.00278334 0.999692 - 0.99705 = 0.0026424 0.999717 - 0.997192 = 0.0025244 0.999724 - 0.997328 = 0.00239658 0.999746 - 0.997457 = 0.00228939 0.999753 - 0.997579 = 0.00217349 0.999772 - 0.997696 = 0.00207614 0.999779 - 0.997808 = 0.00197105 0.999796 - 0.997913 = 0.00188264 0.999802 - 0.998014 = 0.00178736 0.999817 - 0.99811 = 0.00170708 0.999822 - 0.998202 = 0.0016207 0.999836 - 0.998288 = 0.0015478 0.999841 - 0.998371 = 0.0014695 0.999853 - 0.99845 = 0.00140331 0.999857 - 0.998525 = 0.00133233 0.999868 - 0.998596 = 0.00127225 0.999872 - 0.998664 = 0.00120791 0.999882 - 0.998729 = 0.00115337 0.999885 - 0.99879 = 0.00109505 0.999894 - 0.998849 = 0.00104556 0.999897 - 0.998904 = 0.000992697 0.999905 - 0.998957 = 0.000947776 0.999908 - 0.999008 = 0.000899868 0.999915 - 0.999056 = 0.000859103 0.999917 - 0.999101 = 0.000815685 0.999924 - 0.999145 = 0.000778694 0.999926 - 0.999186 = 0.000739347 0.999932 - 0.999226 = 0.000705783 0.999933 - 0.999263 = 0.000670127 0.999939 - 0.999299 = 0.000639675 0.99994 - 0.999333 = 0.000607365 0.999945 - 0.999365 = 0.000579738 0.999946 - 0.999396 = 0.00055046 0.999951 - 0.999425 = 0.000525398 0.999952 - 0.999453 = 0.000498869 0.999956 - 0.99948 = 0.000476135 0.999957 - 0.999505 = 0.000452098 0.99996 - 0.999529 = 0.000431477 0.999961 - 0.999552 = 0.000409699 0.999964 - 0.999573 = 0.000390995 0.999965 - 0.999594 = 0.000371264 0.999968 - 0.999614 = 0.0003543 0.999969 - 0.999632 = 0.000336424 0.999971 - 0.99965 = 0.00032104 0.999972 - 0.999667 = 0.000304845 0.999974 - 0.999683 = 0.000290893 0.999975 - 0.999699 = 0.000276222 0.999977 - 0.999713 = 0.00026357 0.999977 - 0.999727 = 0.000250279 0.999979 - 0.99974 = 0.000238807 0.99998 - 0.999753 = 0.000226767 0.999981 - 0.999765 = 0.000216365 0.999982 - 0.999776 = 0.000205459 0.999983 - 0.999787 = 0.000196027 0.999984 - 0.999798 = 0.000186147 0.999985 - 0.999807 = 0.000177596 0.999985 - 0.999817 = 0.000168647 0.999986 - 0.999826 = 0.000160895 0.999987 - 0.999834 = 0.000152789 0.999988 - 0.999842 = 0.00014576 0.999988 - 0.99985 = 0.000138418 0.999989 - 0.999857 = 0.000132047 0.999989 - 0.999864 = 0.000125396 Indeed, the numeric evidence of convergence is very convincing. But wait a minute... Does this count as a proof? Is it rigorous? The simple answer is, no. Because we can tell that it converges to normal distribution as $n$ goes to infinity, but we still don't know how fast it converges to that! We can tell that for the normal distribution we can stop at a certain $n$, but we don't have proof that the normal distribution is close enough to the actual distributon! Wikipedia states thatIf the third central moment $E[(X_1-\mu)^3]$ exists and is finite, then the speed of convergence is at least on the order of $1/\sqrt{n}$ (see Berry–Esseen theorem). Stein's method can be used not only to prove the central limit theorem, but also to provide bounds on the rates of convergence for selected metrics.Apparently the third central moment is finite for our distribution, but a convergence speed of $1/\sqrt{n}$ is too slow for our problem. The criterion is $10^{-5}$, that would require $10^{10}$ steps, which corresponds to $n=2\times 10^{10}$, larger than the maximum of the constraint! I haven't looked into this "Stein's method", I wonder if it provides a higher lower bound on the speed. Also notice that, we not only need to bound the difference between the probability densities, we also need to bound the difference between the cumulative distribution function, since what we need is the value of the integration. We can also tell that the value approximated by normal distribution seems to be a lower bound of the actual value, except for the first one. But unless we can prove it, it's just an observation. What if we don't use an approximation? What if we just sum up the discrete probabilities? If we use the recursive relationship twice, we get: $p(m,n)=\frac{1}{4}(p(m-4,n)+p(m-3,n-1)+p(m-2,n-2)+p(m-1,n-3))$ $=\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)^2(p(m-8,n)+2p(m-7,n-1)+3p(m-6,n-2)+4p(m-5,n-3)+3p(m-4,n-4)+2p(m-3,n-5)+p(m-2,n-6))$ And the pattern continues. The coefficients goes like this:

1 1 1 1

1 2 3 4 3 2 1

1 3 6 10 12 12 10 6 3 1

1 4 10 20 31 40 44 40 31 20 10 4 1

(more rows up to the 11th:

1,5,15,35,65,101,135,155,155,135,101,65,35,15,5,1,

1,6,21,56,120,216,336,456,546,580,546,456,336,216,120,56,21,6,1,

1,7,28,84,203,413,728,1128,1554,1918,2128,2128,1918,1554,1128,728,413,203,84,28,7,1,

1,8,36,120,322,728,1428,2472,3823,5328,6728,7728,8092,7728,6728,5328,3823,2472,1428,728,322,120,36,8,1,

1,9,45,165,486,1206,2598,4950,8451,13051,18351,23607,27876,30276,30276,27876,23607,18351,13051,8451,4950,2598,1206,486,165,45,9,1,

1,10,55,220,705,1902,4455,9240,17205,29050,44803,63460,82885,100110,112035,116304,112035,100110,82885,63460,44803,29050,17205,9240,4455,1902,705,220,55,10,1,

1,11,66,286,990,2882,7282,16302,32802,59950,100298,154518,220198,291258,358490,411334,440484,440484,411334,358490,291258,220198,154518,100298,59950,32802,16302,7282,2882,990,286,66,11,1,)

On each row, each number is the sum of 4 numbers of the previous row: 2 position to the left of the one above it, 1 position to the left, directly above it, and one to the right, and if it goes out of the boundary, it's considered 0.

Over all, there's an extra coefficient of $\frac{1}{4^t}$ to normalize the probability to one.

Each row has one more element on the left and two more on the right. The vertical line in our figure corresponds to the vertical line of {1,3,10,31...}. If we take the 4th layer of the even cells (coordinate (8,8) in the table below) as an example, the total probability is

$$\frac{1}{4^4}(31\times 0.5 + 40 + 44 + 40 + 31 + 20 + 10 + 4 + 1)=0.802734375$$

(For odd layers, it will recurse back to the row above the line in the figure, so there will be 3 elements multiplied by 0.5. Just a little more complicated.)

This is larger the actual result 0.796875. The reason is simple: When we enter the 0 region, there's a chance that we land at the boundary (coordinate (4,-1)), then there's a 1/4 chance that we enter 0.5, which is impossible since we should already stop once we're outside the grid. There are 3 ways to get to that cell, this gives an extra value of $0.5(3\times \frac{1}{4^3} \times \frac{1}{4})$. Removing this discrepancy gives the correct result.

But as $n$ increases, the discrepancy should converge to 0 exponentially.

So, if we can prove that the sum of the numbers before the middle line converges to zero monotonically, then we're done.

The first few sums are

$$(1 + 0.5)/4 =0.375$$

$$(1+2+3\times 0.5)/4^2=0.28125$$

$$(1+3+6+10\times 0.5)/4^3=0.234375$$

$$(1+4+10+20+31\times 0.5)/4^4=0.197265625$$

If we can find a closed form of this summation, it would be very helpful.

It's easy to find the equation for the first 4 terms from the recurrence relationship. The first is always 1, the second is $t$, the third is $1+\dots+t = t(t+1)/2$, the fourth is $t(t+1)(t+2)/6$ based on the fact $f_4(t)-f_4(t-1)=t(t+1)/2$, the fifth has this recurrence relation $f_5(t)-f_5(t-1)=(t-1)(t^2+4t+6)/6$ and increases as $t^4/24$. So in general, the $k$th term is a polynomial of degree $k-1$ where the coefficient of the leading term is $\frac{1}{(k-1)!}$. It's quite similar to the binomial coefficients, just more complicated. Maybe the techniques to bound the partial sum of binomial coefficients can be applied here, too. We're basically trying to bound the sum of the first $t+1$ (or $t+2$ for odd layers) terms of these unnamed coefficients, where the length of the row is $3t+1$. Based on the fact that it's less than the Gaussian distribution approximation, maybe the Chernoff bound can be applied here, too. This seems to be the most promising direction. I'll take a look at these when I have more time...

[2023 08 03 update] I figured out how to prove the upper bound after giving it a litte more thought! So, basically the idea is (Thanks to user2575jO on leetcode), we can write one step as two steps merged together: choosing from $\{-1,0,1,2\}$ each with $p=1/4$ is equivalent to first choosing from $\{0,2\}$ with $p=1/2$ and then choosing from $\{-1,0\}$ with $p=1/2$, then add the result together. The distributions are exactly the same. Now if we move $t$ steps, the probability that we're at a location $\leq 0$ is $$P(t)=\frac{1}{4^t}\sum_{l=0}^t\left(\binom t l\sum_{r=0}^{l/2}\binom t r\right)$$ where $l$ is the number of $-1$ moves and $r$ is the number of $+2$ moves. $l$ can be from 0 to $t$, and $r$ must be between $0$ and $\frac{l}{2}$, so that the final location $-l+2r\leq 0$. Knowing that $r\leq \frac{t}{2}$, we can apply the Chernoff bound directly (with $p=\frac{1}{2}$): $$Pr\left(r<\frac{l}{2}\right)=Pr\left(r<\frac{t}{2}-\left(\frac{t}{2}-\frac{l}{2}\right)\right)\leq\exp{\left(-2t\left(\frac{\frac{t}{2}-\frac{l}{2}}{t}\right)^2\right)}$$ $$Pr\left(r<\frac{l}{2}\right)\leq\exp{\left(-\frac{(t-l)^2}{2t}\right)}$$ Replace $2^{-t}\sum_{r=0}^{l/2}\binom t r$ with the upper bound above, now we have $$P(t)\leq 2^{-t}\sum_{l=0}^t\binom t l\exp{\left(-\frac{(t-l)^2}{2t}\right)}$$ To simplify this expression, noticing the binomial coefficient, we really want to write the last term as a power of $l$. Let's expand it: $$P(t)\leq 2^{-t}\sum_{l=0}^t\binom t l\exp{\left(-\frac{t^2-2lt+l^2}{2t}\right)}=2^{-t}e^{-t/2}\sum_{l=0}^t\binom t l e^l e^{-\frac{l^2}{2t}}$$ We are almost there, except for the annoying $e^{-\frac{l^2}{2t}}$ term. It's a normal distribution, centered at 0. If we can bound it by some function like $a e^{-bl}$, then we can write the term as a power of $l$. And that seems doable! $$e^{-\frac{l^2}{2t}}\leq ae^{-bl}$$ $$e^{-\frac{l^2}{2t}+bl}\leq a$$ $$e^{-\frac{1}{2t}(l-bt)^2+b^2t/2}\leq a$$ If we choose $a=e^{b^2t/2}$, the inequality is always true. Apply this inequality with an arbitrary $b$, we get $$P(t)\leq 2^{-t}e^{-t/2}\sum_{l=0}^t\binom t l e^l e^{b^2t/2} e^{-bl}$$ $$=2^{-t}e^{-t/2}e^{b^2t/2}\sum_{l=0}^t\binom t l e^l e^{-bl}$$ $$=2^{-t}e^{\frac{b^2-1}{2}t}\left(1+e^{1-b}\right)^t$$ $$=\left(\frac{1}{2}\left(e^{\frac{b^2-1}{2}}+e^{\frac{(b-1)^2}{2}}\right)\right)^t$$ Now we want to choose a $b$ to minimize this expression. Taking the derivative and we find this equation $$be^{b-1}+b-1=0$$ Solving it numerically, we find $$b=0.598942$$ Putting it back to the inequality above, we get $$P(t)\leq 0.9047174^t$$ The threshold is at $$0.9047174^t=10^{-5}$$ $$t=114.97\dots$$ Remember that $t$ is the number of steps, so this corresponds to $n=2t=230$, the same result as the Gaussian approximation above! (Probably not a coincidence, because even though they are very different for small $n$s, when I change $10^{-5}$ to $5\times 10^{-6}$, they still give the same result $n=244$. I think this has the same asymptotic behavior as the Gaussian approximation.) But this time the bound is proved. (The $l$ should be replaced by $l+1$ or $l+2$ somewhere, because the value in the middle is 0.5, not 1, and in odd layers it recurses back to the layer of three 0.5s, so we must shift it one more step. But these are just small details, it shouldn't change the answer by much...) [update end]

What else can we do, then? In the previous calculations, we're trying to find an upper bound. If we have an upper bound, we can use that to estimate where to stop, e.g. if we can prove that the normal distribution is an upper bound, we cau use the threshold $n=230$. But if we can prove the monotonicity, we can use the threshold at exactly where the value exceeds the criterion i.e. $n=179$, which is a stronger statement. Let's go back to the grid, maybe. The proof would be trivial if all the values increase monotonically along any vertical line. But unfortunately that is not the case. The elements in the top $10 \times 10$ grid are

0.625, 0.75, 0.875, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1,

0.5, 0.625, 0.75, 0.90625, 0.9375, 0.96875, 1, 1, 1, 1,

0.375, 0.5, 0.65625, 0.8125, 0.875, 0.9375, 0.976562, 0.984375, 0.992188, 1,

0.25, 0.40625, 0.5625, 0.71875, 0.8125, 0.890625, 0.9375, 0.960938, 0.984375, 0.994141,

0.15625, 0.3125, 0.46875, 0.625, 0.742188, 0.828125, 0.890625, 0.9375, 0.966797, 0.980469,

0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.53125, 0.65625, 0.757812, 0.84375, 0.902344, 0.9375, 0.960938,

0.09375, 0.1875, 0.304688, 0.453125, 0.578125, 0.6875, 0.785156, 0.851562, 0.900391, 0.941406,

0.0625, 0.140625, 0.25, 0.382812, 0.5, 0.617188, 0.71875, 0.796875, 0.863281, 0.912109,

0.0390625, 0.109375, 0.203125, 0.3125, 0.429688, 0.546875, 0.652344, 0.742188, 0.817871, 0.87207,

0.03125, 0.0859375, 0.15625, 0.253906, 0.367188, 0.480469, 0.585938, 0.683594, 0.763672, 0.827637,

The diagonal line is indeed increasing, but the third diagonal line has elements 0.875, 0.90625, 0.875, 0.890625, 0.890625, 0.902344, 0.900391, 0.912109... which increases and decreases alternately. And that is not the only diagonal line that shows this behavior. Let's take the 5th diagonal line as an example, the first few elements are

1, 1,0.984375,0.984375,0.980469,0.980469,0.978516,0.979492,0.978271,0.979492,

0.979004,0.980286,0.980179,0.981461,0.981567,0.982796, 0.98303, 0.98418,0.984484,0.985547,

0.985884,0.986855,0.987203,0.988086, 0.98843,0.989229, 0.98956,0.990281,0.990595,0.991244,

0.991538, 0.99212,0.992393,0.992915,0.993167,0.993635,0.993865,0.994284,0.994495, 0.99487,

0.995062,0.995397,0.995572,0.995872, 0.99603,0.996298,0.996441,0.996681, 0.99681,0.997024,

It's not easy to tell if it increases or decreases. Let's see their differences:

0, -0.015625, 0, -0.00390625, 0, -0.00195312, 0.000976562, -0.0012207, 0.0012207,-0.000488281,

0.00128174,-0.000106812, 0.00128174, 0.000106812, 0.00122833, 0.000234604, 0.00115013, 0.000303984, 0.00106215, 0.000337005,

0.000971675, 0.000347495, 0.000883162, 0.000343844, 0.000799075, 0.000331543, 0.000720632, 0.000314187, 0.00064834, 0.00029413,

0.000582274, 0.000272915, 0.000522257, 0.000251551, 0.00046797, 0.00023068, 0.000419023, 0.000210703, 0.000374994, 0.000191853,

It alternates for about 12 times, then it keeps increasing. Remembering that there are two independent sets of layers, we should find the differences within each set. The differences within the odd layers are

-0.015625, -0.00390625, -0.00195312,-0.000244141, 0.000732422, 0.00117493, 0.00138855, 0.00146294, 0.00145411, 0.00139916, 0.00131917, 0.00122701, 0.00113062, 0.00103482, 0.00094247, 0.00085519, 0.000773808, 0.000698651, 0.000629726, 0.000566848,

and the even layers

-0.015625, -0.00390625,-0.000976562, 0, 0.000793457, 0.00117493, 0.00133514, 0.00138474, 0.00136614, 0.00130868, 0.00123066, 0.00114292, 0.00105218, 0.000962528, 0.000876404, 0.000795173, 0.000719521, 0.000649703, 0.000585698, 0.000527314,

Now they no longer alternate. Is it possible to prove that it can only decrease for a finite amount of times before it starts to increase monotonically? Let's take a look at a diagonal line that's further away. Here are the differences of the elements on the 10th diagonal:

odd layers:

0,-0.000488281,-0.000488281,-0.000366211,-0.000267029,-0.000171661,-9.20296e-05, -3.0756e-05, 1.508e-05, 4.81904e-05,

7.11586e-05, 8.62759e-05, 9.54153e-05, 0.000100072, 0.000101421, 0.000100375, 9.7634e-05, 9.37348e-05, 8.9083e-05, 8.39835e-05,

even layers:

0,-0.000366211,-0.000427246,-0.000335693,-0.000244141,-0.000161171,-9.08375e-05,-3.57032e-05, 5.90086e-06, 3.63067e-05,

5.7715e-05, 7.20862e-05, 8.10546e-05, 8.59372e-05, 8.77771e-05, 8.73906e-05, 8.54098e-05, 8.23208e-05, 7.84945e-05, 7.42116e-05,

It seems that the further away from the middle, the more times it would decrease. Let's see if we can find out more about this pattern! In the following two figures (first the odd layers, second the even layers), a cell $(m,n)$ is a black square if $p(m,n)-p(m-2,n-2)$ is negative, a white square if positive, and a dash if zero.

There is definitely a pattern here. The boundary between increasing cells and decreasing cells shifts further and further away from the middle diagonal line. If this can be proved, then it's obvious that the diagonal line doesn't have decreasing cells. But I haven't found a proof of that. How about we consider something more solid - something that we can actually prove? If we look at the table again, it's easy to see that the values increase rightward and decrease downward. Can we do better than that? It's easy to see that the number on the left boundary decrease to $1/4$ of the value 4 steps (or 1 layer) above it. We can also tell that there are more and more 1s on the right boundary. Let's mark them on the figure:

The value of the light green cell is 1/4 of the green cell, whose value is 1/4 of the deep green cell. With the same reasoning, we can tell that there's a similar pattern on the right boundary. There is one more cell of value 1 after each layer, and also the value of the cell next to the 1 (the blue cells) increases monotonically downward. The difference between 1 and the value of the blue cell is 1/4 of the difference between 1 and the light blue cell, and the difference between 1 and and the deep blue cell is 1/4 of the previous one. So the value of the cells along this line converges to 1. By induction, it's easy to show that any cell increases value along that line downward. So we have two lines that guarantee to increase or decrease downward. Is there a line of equal values, then? If so, any angle between the increasing line and equal line should be increasing, and the other angles should be decreasing. But the angle of the equal line depends on where the cell is, because if the cell already has value 1, the equal line is the same as the increasing line. So as the location of the cell changes from the right most to the left most, the angle between the equal line and the increasing line increases from 0 to some positive value. The two figures above seems to support this statement. If we can prove that when the cell is in the middle, the equal line always points to the lower left, then we can tell that along the middle diagonal, the value increases monotonically. Another thing that I noticed is, the summation of the values on the next layer is always 2.5 larger than the current layer, since all the values will appear exactly 4 time in the average, the extra 0s don't contribute, and the 1s contribute exactly $(4+3+2+1)/4=2.5$ to the summation of the next layer. I don't know how to use this fact in a proof, though. Anyway, this summarizes my thoughts on this problem so far. If anyone finds a rigorous proof of this problem, I'd be glad to hear it!